Biodiversity and Sustainability Advisory Committee Meeting

A Biodiversity and Sustainability

Advisory Committee Meeting of Byron Shire Council will be held as follows:

|

Venue

|

Conference Room, Station Street, Mullumbimby

|

|

Date

|

Thursday, 18 February 2016

|

|

Time

|

9.00am

|

Shannon Burt

Director Sustainable Environment and Economy I2016/58

Distributed 11/02/16

What is a “Conflict of Interests” - A conflict of

interests can be of two types:

Pecuniary - an interest that a person has in a matter because of a reasonable

likelihood or expectation of appreciable financial gain or loss to the person

or another person with whom the person is associated.

Non-pecuniary – a private or personal interest that a Council

official has that does not amount to a pecuniary interest as defined in the

Local Government Act (eg. A friendship, membership of an association, society

or trade union or involvement or interest in an activity and may include an

interest of a financial nature).

Remoteness – a person does not have a pecuniary interest in a matter

if the interest is so remote or insignificant that it could not reasonably be

regarded as likely to influence any decision the person might make in relation

to a matter or if the interest is of a kind specified in Section 448 of the

Local Government Act.

Who has a Pecuniary Interest? - a person has a pecuniary interest in a

matter if the pecuniary interest is the interest of the person, or another

person with whom the person is associated (see below).

Relatives, Partners - a person is taken to have a pecuniary interest in a

matter if:

§ The person’s

spouse or de facto partner or a relative of the person has a pecuniary interest

in the matter, or

§ The person, or a

nominee, partners or employer of the person, is a member of a company or other

body that has a pecuniary interest in the matter.

N.B. “Relative”, in relation to a person means any of the

following:

(a) the

parent, grandparent, brother, sister, uncle, aunt, nephew, niece, lineal

descends or adopted child of the person or of the person’s spouse;

(b) the

spouse or de facto partners of the person or of a person referred to in

paragraph (a)

No Interest in the Matter - however, a person is not taken to have a

pecuniary interest in a matter:

§ If the person is

unaware of the relevant pecuniary interest of the spouse, de facto partner,

relative or company or other body, or

§ Just because the

person is a member of, or is employed by, the Council.

§ Just because the

person is a member of, or a delegate of the Council to, a company or other body

that has a pecuniary interest in the matter provided that the person has no

beneficial interest in any shares of the company or body.

Disclosure and participation in meetings

§ A Councillor or a

member of a Council Committee who has a pecuniary interest in any matter with

which the Council is concerned and who is present at a meeting of the Council

or Committee at which the matter is being considered must disclose the nature

of the interest to the meeting as soon as practicable.

§ The Councillor or

member must not be present at, or in sight of, the meeting of the Council or

Committee:

(a) at any

time during which the matter is being considered or discussed by the Council or

Committee, or

(b) at any

time during which the Council or Committee is voting on any question in

relation to the matter.

No Knowledge - a person does not breach this Clause if the person did

not know and could not reasonably be expected to have known that the matter

under consideration at the meeting was a matter in which he or she had a

pecuniary interest.

Participation in Meetings Despite Pecuniary Interest (S 452 Act)

A Councillor is not prevented from taking part in the consideration or

discussion of, or from voting on, any of the matters/questions detailed in

Section 452 of the Local Government Act.

Non-pecuniary Interests - Must be disclosed in meetings.

There are a broad range of options available for managing conflicts &

the option chosen will depend on an assessment of the circumstances of the

matter, the nature of the interest and the significance of the issue being

dealt with. Non-pecuniary conflicts of interests must be dealt with in at

least one of the following ways:

§ It may be appropriate

that no action be taken where the potential for conflict is minimal.

However, Councillors should consider providing an explanation of why they

consider a conflict does not exist.

§ Limit involvement if

practical (eg. Participate in discussion but not in decision making or

vice-versa). Care needs to be taken when exercising this option.

§ Remove the source of

the conflict (eg. Relinquishing or divesting the personal interest that creates

the conflict)

§ Have no involvement by

absenting yourself from and not taking part in any debate or voting on the

issue as if the provisions in S451 of the Local Government Act apply

(particularly if you have a significant non-pecuniary interest)

RECORDING OF VOTING ON PLANNING MATTERS

Clause 375A of the Local Government Act 1993

– Recording of voting on planning matters

(1) In this section, planning

decision means a decision made in the exercise of a function of a council

under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979:

(a) including a decision

relating to a development application, an environmental planning instrument, a

development control plan or a development contribution plan under that Act, but

(b) not including the making of

an order under Division 2A of Part 6 of that Act.

(2) The general manager is

required to keep a register containing, for each planning decision made at a

meeting of the council or a council committee, the names of the councillors who

supported the decision and the names of any councillors who opposed (or are

taken to have opposed) the decision.

(3) For the purpose of maintaining

the register, a division is required to be called whenever a motion for a

planning decision is put at a meeting of the council or a council committee.

(4) Each decision recorded in

the register is to be described in the register or identified in a manner that

enables the description to be obtained from another publicly available

document, and is to include the information required by the regulations.

(5) This section extends to a

meeting that is closed to the public.

Biodiversity and Sustainability Advisory Committee

Meeting

BUSINESS OF MEETING

1. Apologies

2. Declarations of Interest

– Pecuniary and Non-Pecuniary

3. Adoption of Minutes from

Previous Meetings

3.1 Biodiversity

and Sustainability Advisory Committee Meeting held on 12 November 2015

4. Business Arising From

Previous Minutes

5. Staff Reports

Sustainable Environment and Economy

5.1 Environmental

Levy Budget ............................................................................................. 4

5.2 High

Conservation Value (HCV) and Office of Environment and Heritage's High

Environmental Value (HEV) methodology.............................................................................................. 13

5.3 Wildlife

Corridor Mapping................................................................................................ 22

Staff Reports - Sustainable Environment and Economy 5.1

Staff Reports - Sustainable Environment and

Economy

Report No. 5.1 Environmental

Levy Budget

Directorate: Sustainable

Environment and Economy

Report

Author: Sharyn

French, Manager Environmental and Economic Planning

File No: I2015/343

Theme: Ecology

Planning Policy and Natural Environment

Summary:

This report provides information on the projects funded by

the Environmental Levy in accordance with Council’s policy.

|

RECOMMENDATION:

That the

Biodiversity and Sustainability Advisory Committee note this report.

|

Attachments:

1 Policy

Environmental Levy Implementation No 15/003 adopted afer close of

exhibition 7/5/2015 Res No. 15-094, E2015/31373

, page 7

Report

Council’s adopted

Environmental Levy Implementation Policy, Attachment 1, states:

5. POLICY STATEMENT

5.1. The Biodiversity and

Sustainability Advisory Committee will review the allocation of funds from the

Environmental Levy, namely by:

a)

Providing advice to Council on matters to be considered for funding from the Environmental

Levy each year

b)

Reviewing the projects funded by the Environmental levy on a quarterly basis, following

advice provided by Council staff and report progress to Council

c)

Reviewing annually the draft budget for expenditure of the Environmental Levy

and providing advice to Council on both the allocation and expenditure of funds

consistent with the Environmental Levy Terms of Reference including

prioritisation and monitoring environmental outcomes of Levy funded projects

The following information

on the 2015/16 allocation and expenditure of the Environmental Levy is provided

for the Committees consideration.

Table 1: 2015/16 Environmental Levy allocation and

expenditure

|

Activity

|

2015/16

Allocation $

|

Expenditure to

31 January 2016

|

Comment

|

|

Staff wages

|

236,200

|

130,500

|

Funds Bush Regeneration

Team, Environmental Administration Office and partly funds Coastal Estuary

Officer and Sustainability Officer

|

|

Operational Costs - Bush

Regeneration Team

|

5,200

|

3,497

|

Purchase of tools and

supplies

|

|

Community Infrastructure Maintenance

Program

|

9,200

|

954

|

Allocated to implementation

of Roadside Vegetation Management Plan

|

|

CZMP for Byron Bay

Embayment

|

39,900

|

38,084

|

Allocated to contract with

Water Research Laboratory for preparation of the Coastal Hazard Management

Study Byron Bay Embayment

|

|

Feral animal control program

|

12,500

|

850

|

Allocated to trapping

program in conjunction with Koala Connections project and Local Land

Services.

|

|

Low Carbon Strategy

|

10,000

|

500

|

Allocated to implementation

of priority Low Carbon Strategy actions.

|

|

Land for Wildlife Program

|

17,100

(c/o 2014/15)

|

3,815

|

Council’s

contribution to $98,000 NSW Environmental Trust grant, a 3 year project

commenced January 2015.

|

|

Bangalow Waterfront

Environmental Works

|

24,300

(c/o 2014/15)

|

500

|

Riparian restoration works

associated with removal of Bangalow weir.

|

|

Vegetation Mapping Stage 2

|

20,000

(c/o 2014/15)

|

18,771

|

Allocated to consultants

engaged in mapping review.

|

|

Flying Fox Plan of

Management

|

33,300

|

10,225

|

Allocated to development of

Mullumbimby Flying Fox Plan and implementation of high priority actions.

|

|

TOTAL

|

407,700

|

207,696

|

|

Council has commenced budget preparations for the 2016/17

financial year. In February and March, staff will finalise compiling the first

draft 2016/17 budget for Councillors consideration at a Strategic Planning

Workshop in late March and reporting to Council in early April. The draft

budget will be exhibited in April/May for adoption by Council in June.

Less staff wages, there are approximately $156,000

Environmental Levy funds available to deliver projects in 2016/17. These funds

are proposed to be disbursed to the following projects:

· Biodiversity and

Conservation Strategy review - $20,000

· Updating

vegetation mapping with 2015 high resolution aerial imagery- $61,400

· Low Carbon

Strategy actions - $13,000

· Coastal Zone

Management Plan actions (excluding ‘coastal protection works’)

$39,900

· Roadside

Vegetation Management Plan - $9,200

· Wild dog and feral

animal control - $12,500

In line with the Environmental Levy Implementation Policy,

the Biodiversity and Sustainability Committee should consider providing advice

to Council on matters to be considered for funding from the Environmental Levy.

Financial Implications

The eventual budget

determined for the Environmental Levy for 2016/17 will be resolved by Council

in June 2016.

Statutory and Policy Compliance Implications

Nil

Staff Reports - Sustainable Environment and Economy 5.1 - Attachment 1

BYRON SHIRE COUNCIL

POLICY NO. 15/003

Environmental Levy

Implementation

E2015/31373

Staff Reports - Sustainable Environment and Economy 5.1 - Attachment 1

INFORMATION

ABOUT THIS DOCUMENT

|

Date Adopted by

Council

|

7 May 2015

|

Resolution No.

|

15-094

|

|

Policy Responsibility

|

Manager Land and

Natural Environment

|

|

Review Timeframe

|

As required

|

|

Last Review Date:

|

|

Next Scheduled Review

Date

|

|

Document History

|

Doc No.

|

Date Amended

|

Details Comments eg

Resolution No.

|

|

E2014/44800

|

26 June 2014

|

Draft Version

after Res 14-321

|

|

E2014/61683

|

11 September 2014

|

Draft

incorporating Biodiversity & Sustainability Advisory Committee

recommendations (public exhibition version Res 15-94)

|

|

E2015/31373

|

7/5/2015

|

Adopted after close of

exhibition 7/5/2015 as per Res 15-094 no submissions received

|

Further Document

Information and Relationships

|

Related Legislation*

|

Coastal Protection Act 1979

|

|

Related Policies

|

Byron Biodiversity

Conservation Strategy

Byron Low Carbon

Strategy

Coastal Zone Management

Plans

|

|

Related Procedures/

Protocols, Statements, documents

|

|

Note: Any reference to

Legislation will be updated in the Policy as required. See website http://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/ for current Acts, Regulations and Environmental

Planning Instruments.

Staff Reports - Sustainable Environment and Economy 5.1 - Attachment 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. OBJECTIVES............................................................................................................................... 1

2. BACKGROUND........................................................................................................................... 1

3. Principals................................................................................................................................ 1

4. Terms of Reference........................................................................................................... 1

5. POLICY

STATEMENT................................................................................................................. 2

This Page has been

intentionally left blank.

Staff Reports - Sustainable Environment and Economy 5.1 - Attachment 1

Policy No. 15/003

|

POLICY TITLE

|

ENVIRONMENTAL

LEVY IMPLEMENTATION POLICY

|

1. OBJECTIVES

1.1. To

inform the allocation of revenue raised through the Environmental Levy in the

Byron Shire Council local government area.

1.2. To

outline the arrangements for allocating and managing the Environmental Levy

funds

2. BACKGROUND

Byron Shire is well know for its diverse, natural

environment including beautiful coastlines, lush rainforests, creeks, rivers

and mountain ranges which form part of the remnants of the Wollumbin caldera.

These environmental assets are supported by an active and aware community that

values and promotes the protection and enhancement of the environment.

Following the adoption of the Byron Biodiversity

Conservation Strategy in 2004 Council received approval from the NSW government

to apply a special rate variation of 2% for four years to fund a Biodiversity

Levy in order to implement the Byron Biodiversity Conservation Strategy. In

2008, the Biodiversity Levy was replaced with an Environmental Levy that

continues to support the implementation of the Byron Biodiversity Conservation

Strategy as well as Council's sustainability and coastal programs.

The Environment Levy is a key revenue source to assist in the

implementation of Council endorsed environmental plans and strategies. The Levy

has been essential to the successes achieved through the implementation of a

range of biodiversity, coastal and sustainability programs and enabled Council

to leverage significant additional funding via external grants.

3. Principles

The Environmental Levy is to be used to fund activities

which either:

3.1. Identify,

maintain, protect or enhance native biodiversity, ecosystems and ecological

processes.

3.2. Reduce

Byron Shire’s greenhouse gas emissions or improve the environmental

sustainability and resilience of Council and the community.

3.3. Undertake

studies and prepare plans for coastal processes, values and risks and implement

those actions that address protecting or enhancing coastal biodiversity,

ecosystems and ecological processes.

4. Terms of Reference

The

Environmental Levy will only be used to fund staff, priority actions and

projects consistent with:

4.1. Developing

and/or delivering the Byron Biodiversity Conservation Strategy

4.2. Developing

and/or delivering the Roadside Vegetation Management Plan

4.3. Developing

and/or delivering the Byron Shire Low Carbon Strategy

4.4. Developing

Coastal Zone Management Plans (CZMP), including estuary management plans, and

delivering actions that are consistent with the above Principles, and/or the

objectives of the above strategies, but not the implementation of ‘coastal

protection works’ as defined under the Coastal Protection Act 1979[1].

5. POLICY STATEMENT

5.1. The

Biodiversity and Sustainability Advisory Committee will review the allocation

of funds from the Environmental Levy, namely by:

a) Providing advice

to Council on matters to be considered for funding from the Environmental Levy

each year

b) Reviewing the

projects funded by the Environmental levy on a quarterly basis, following

advice provided by Council staff and report progress to Council

c) Reviewing annually

the draft budget for expenditure of the Environmental Levy and providing advice

to Council on both the allocation and expenditure of funds consistent with the

Environmental Levy Terms of Reference including prioritisation and monitoring

environmental outcomes of Levy funded projects

5.2. All

funds collected including any funds raised through Environment Levy business

activities is held and accounted for separately from Council’s general

revenue.

5.3. Environment

Levy funds should not be available at any time for expenditure as general

revenue in accordance with principles of the Environmental Levy.

5.4. Any

unspent funds at the end of financial year are to be returned to the

Environment Levy budget.

5.5. The

Environment Levy can be used for leveraging funding through grants and

partnership opportunities offered by government and other organisations.

5.6. Funds

from the Environment Levy may be quarantined or saved annually in order to

compound funds over subsequent years to raise a larger sum of funds for

designated projects or matching grants.

Staff Reports - Sustainable Environment and Economy 5.2

Report No. 5.2 High

Conservation Value (HCV) and Office of Environment and Heritage's High

Environmental Value (HEV) methodology

Directorate: Sustainable

Environment and Economy

Report

Author: Sharyn

French, Manager Environmental and Economic Planning

File No: I2015/1501

Theme: Ecology

Planning Policy and Natural Environment

Summary:

The methodology used to derive Council’s High

Conservation Value (HCV) vegetation, known as the Relative Ecological Values

Matrix (REVM), is redundant. Some of the data sets used to inform HCV are no

longer supported and the methodology is no longer considered current best

practice. The Office of Environment and Heritage has developed a state

wide model to map High Environmental Values (HEV). The HEV model has been used

to inform the Department of Planning’s Draft North Coast Regional Plan

(to be released for comment in early 2016). This plan will replace the

current Far North Coast Regional Strategy that Councils are required to

consider when preparing local land use strategies.

The Office of Environment and Heritage’s HEV model

will be used to inform the preparation of Council’s draft Rural Land Use

Strategy, providing a consistent northern NSW approach to the identification of

land with high environmental values and in accordance with the state

government’s regional plan.

|

RECOMMENDATION:

That the Biodiversity and Sustainability

Committee note this report.

|

Attachments:

1 Relative

Ecological Value Matrix (REVM) used to derive HCV, E2015/81496 , page 17

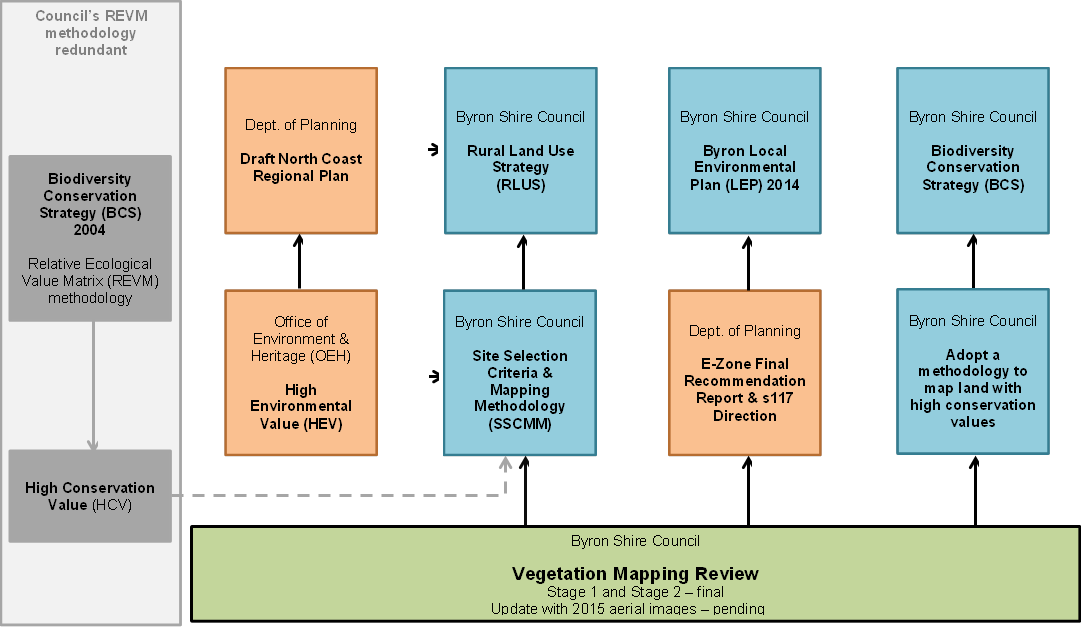

2 Figure 1.

Relationship of vegetation mapping review to other projects, E2015/81622 ,

page 21

3 Confidential

- Office of Environment & Heritage HEV High Environmental Value Methodology

, E2015/81916

Report

Rural Land Use Strategy

Council at the 29 October 2015 meeting resolved (15-569) to

endorse the Site Suitability Criteria and Mapping Methodology (SSCMM) as a key

document to inform preparation of the Rural Land Use Strategy.

The SSCMM included land with HCV as a constrained matter,

thereby excluding it from future rural development.

Council at the 10 December 2015 meeting considered the

endorsed the Rural Land Use Strategy Site Selection Criteria and Mapping

Methodology and related maps and resolved to note that the ‘HCV’

mapping will be presented in conjunction with the draft Strategy to Council in

early 2016 for adoption.

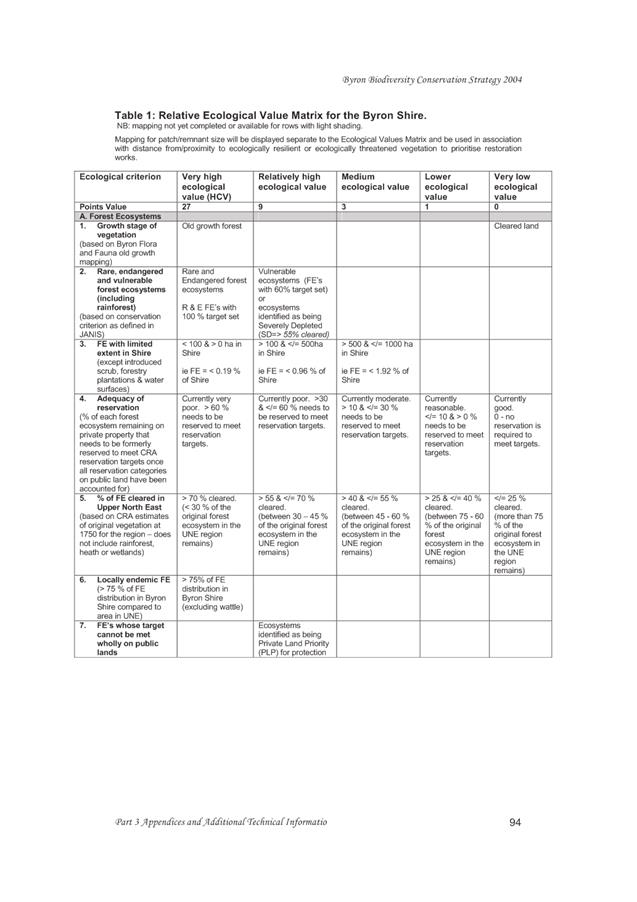

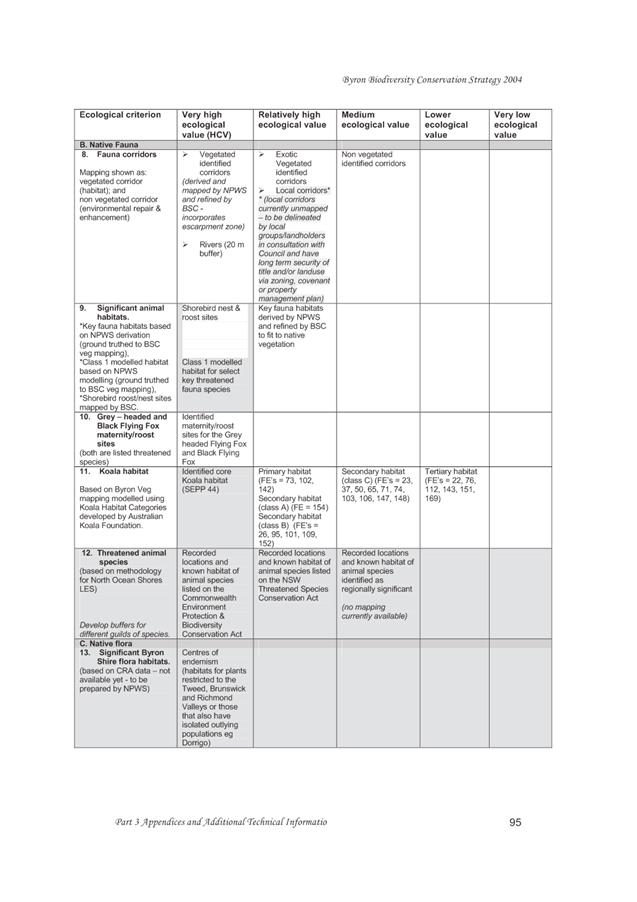

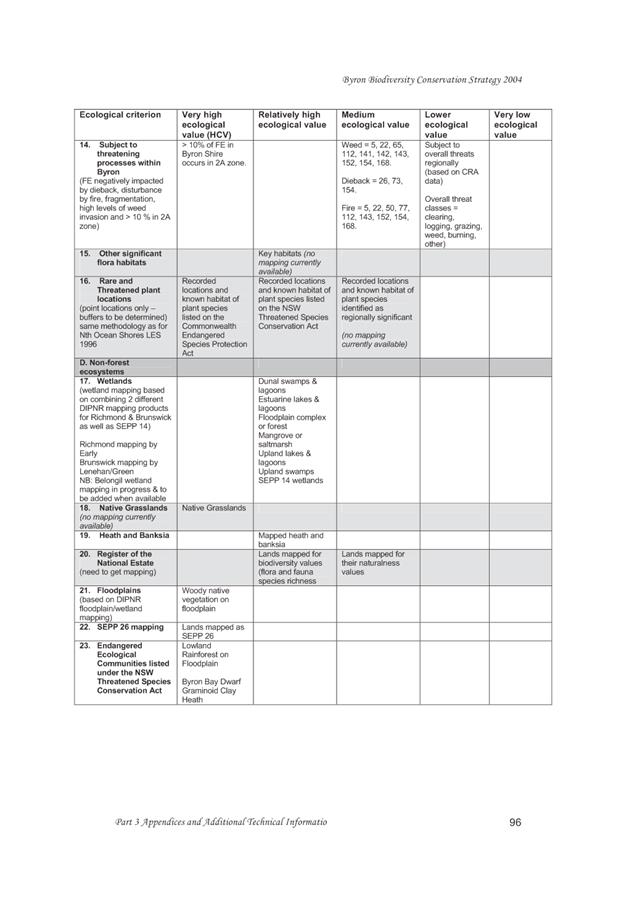

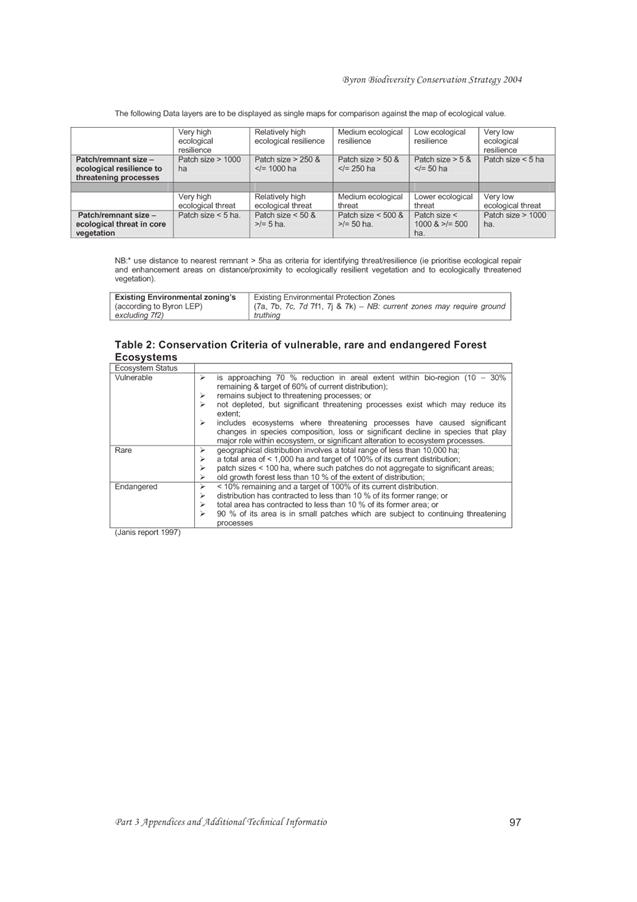

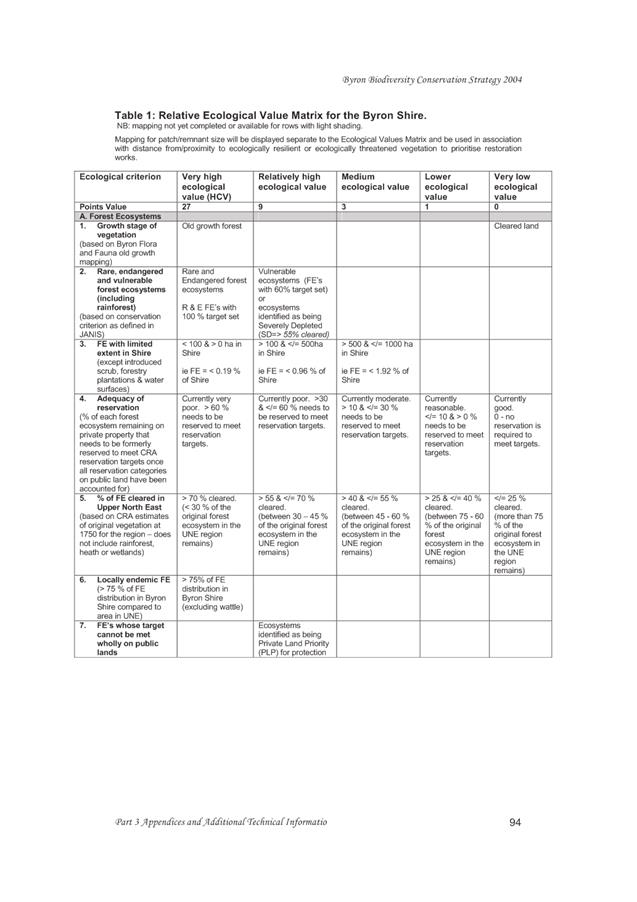

Relative Ecological

Value Matrix (REVM)

The REVM used to derive HCV was prepared over 10 years ago

as part of the Byron Biodiversity Conservation Strategy, 2004. Attachment

1 contains a copy of the ecological criteria used to inform the HCV map

layer. Areas with a combined score of 27 or more are regarded

as HCV.

Vegetation Mapping

Review

In 2015, Council commenced a review of the

vegetation mapping. Vegetation mapping was initially carried out in 1999 as

part of the Byron Flora and Fauna Study and was partly reviewed in 2007.

The review has improved the accuracy of the mapping and reflects changes in

vegetation extent and composition over time.

The review used a combination of aerial

photograph interpretation (API) primarily using 2014 aerial data, existing

information such as, vegetation survey data from various Council and state

government projects, and on-ground site inspections.

Vegetation was mapped using the State

Government’s Vegetation Information System (VIS) Classification database

to ensure consistency with NSW standards. This system uses three levels;

vegetation formations, vegetation classes and plant community types. The plant

community type classification provides the most detailed description of

vegetation and was developed by the state government to provide a standard approach

to vegetation classification and mapping.

The revised vegetation mapping for Stage 1

coastal lowlands and Stage 2 remainder of the Shire, have been publicly

exhibited and are now final. However, before reporting the final results,

Council resolved (15- 417) that following public exhibition of Stage 2

the vegetation mapping for both Stages 1 and 2 be reviewed against the

2015 Hi-Res Imagery from Land and Property Information (LPI) prior to

reporting back to Council. Council has now received the new 2015 aerial

imagery from LPI. Funding to review the vegetation maps against the 2015 aerial

imagery will need to be considered in the 2016/17 budget process.

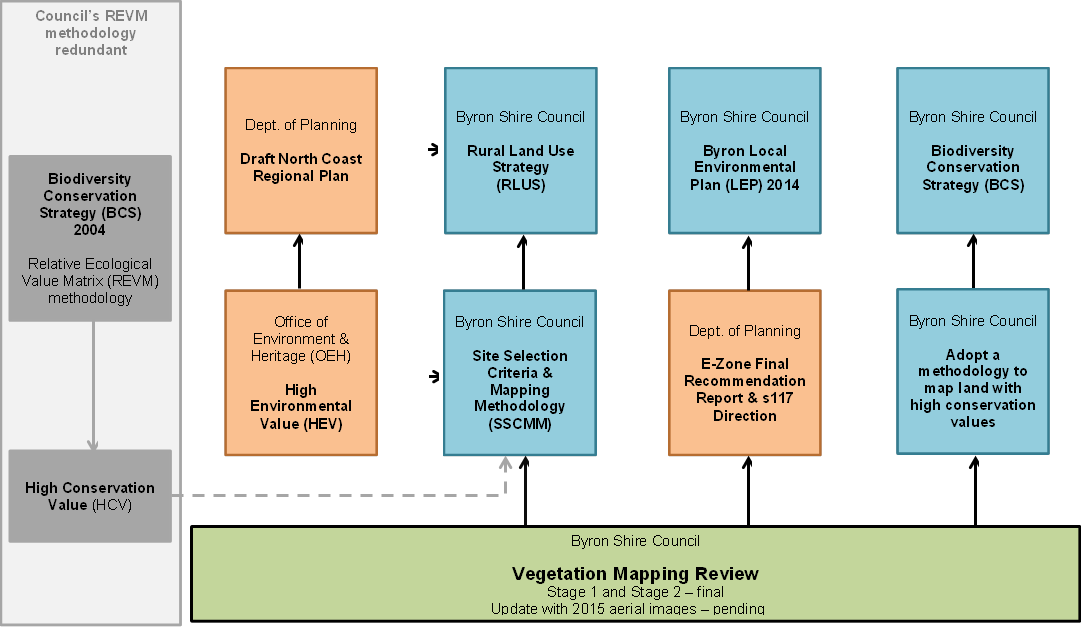

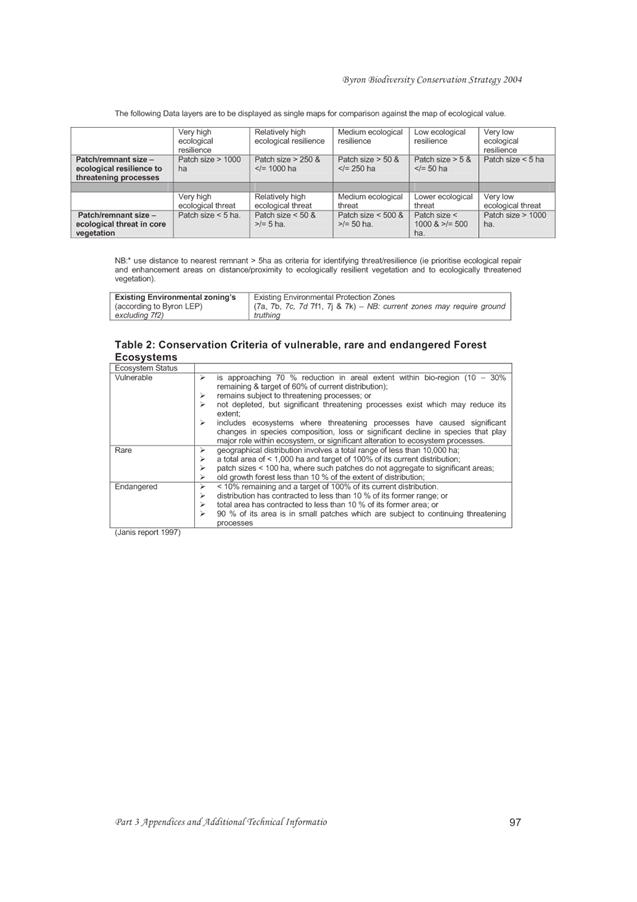

The vegetation mapping review data will be used to inform

several pieces of work including the Rural Land Use Strategy, E Zones, and the

review of the Biodiversity Conservation Strategy, see Attachment 2,

Figure 1 which shows the relationship of the vegetation mapping to these

projects.

Office of Environment and Heritage’s High

Environmental Value (HEV) Methodology

The Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) have produced a

methodology to identify land with high environmental values. Known as the

HEV methodology this has been used by the Department of Planning in the Draft

North Coast Regional Plan (to be released for comment in early 2016).

This plan will replace the current Far North Coast Regional Strategy

that Councils’ are required to consider when preparing local strategies

such as the Rural Land Use Strategy.

Confidential Attachment 3 lists the criteria

to be used in preparing a HEV map.

REVM/HCV versus HEV methodology

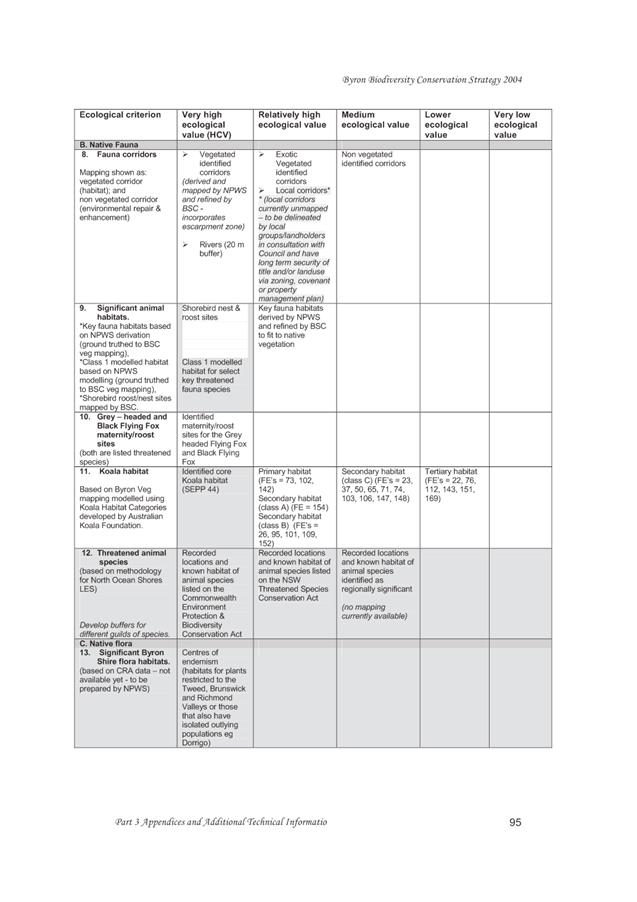

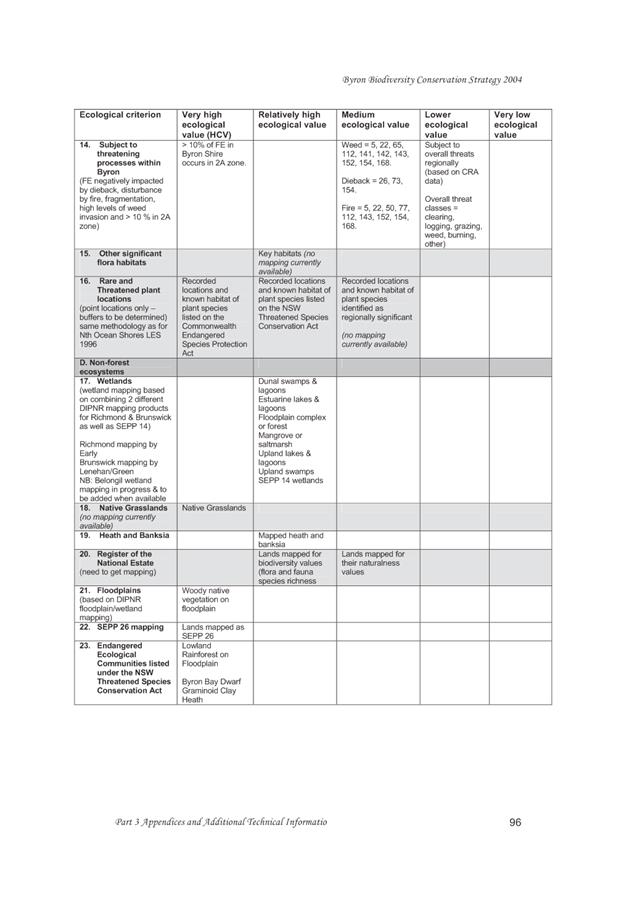

In reviewing the REVM methodology to update the HCV layer

with the new vegetation data, a number of issues became apparent. Most

significantly, the Forest Ecosystems types, used in the REVM, is out-dated and

no longer supported. The REVM was heavily based on Forest Ecosystem types which

are limited in relevance (as they excluded rainforest and non-forest

vegetation) and are out of date (their conservation significance is based

partly on their reservation status which has changed over time).

Additionally, and in comparing the two models (HCV and HEV) the following

issues were identified:

· there is still no

mapping available to complete those fields in the REVM that were marked as

having no mapping available in 2004. These are the fields shaded in light

grey in Attachment 1.

· the

2015 vegetation mapping review used the State

Government’s Vegetation Information System (VIS) Classification ensures

Council follows a state wide consistent approach. VIS doesn’t support the

outdated Forest Ecosystem types; it doesn’t translate its vegetation

categories into Forest Ecosystems and cannot be attempted as there are

vegetation categories that have no equivalent Forest Ecosystem.

· vegetation

classification, as used by VIS, has moved towards using Plant Community Types

and Keith classes. Office of Environment’s HEV method fits with the

approach used in Native Vegetation Plans and Biobanking, which rely on Plant

Community Type classifications. In addition, the OEH methodology

recognises private land with conservation commitments, riparian vegetation and

key habitats. It may also tie in more easily with the state

government’s E Zone criteria.

· the

plant community typing, the third and most detailed level used in VIS, is a

work in progress. Whilst there are some vegetation types that have no current

classification, OEH have a process to assess and determine new plant community

types. Byron’s vegetation mapping review identified potential new

plant community types and some issues with the existing plant community

descriptions for north-eastern NSW. These matters will be referred to

OEH. Whilst there may be difficulties in using an incomplete plant

community type classification for the purposes of HEV modelling, it is

preferable to the use of Forest Ecosystems and should serve well into the

future as new information becomes available the mapping can be readily updated.

· whilst the HEV

model does not consider wildlife corridors (as does the REVM model), Council

could chose to map wildlife corridors as a separate layer at a future stage.

Council’s Biodiversity and Sustainability Committee are reviewing

Council’s wildlife corridor methodology as part of the Biodiversity Conservation

Strategy review. Information resulting from this review will be provided to

Council in due course for consideration.

· it seems likely

that the HEV model would pick up the areas identified as HCV in the 2004

Biodiversity Strategy, and there may be an expansion of high environmental

value land across the Shire as a result of concerted community efforts to

restore the land

· the HEV riparian

buffers are based on 3rd order streams. The current Byron-Tweed

drainage layer is in some instances up to 30m out, as such any application of

buffers to this line cannot be satisfactory. The layer will need to be updated

by air photo interpretation and GIS and re-aligned prior to identifying

vegetation within 40m of streams. This could form part of a future HEV mapping

update.

Conclusion

The REVM/HCV methodology is redundant. The Office of

Environment and Heritage have developed a model to identify land with high

environmental values. Known as the HEV model, it has been used by the

Department of Planning to inform the soon to be released Draft North Coast

Regional Plan. Council’s local strategies such as the Draft Rural

Land Use Strategy need to be consistent with regional plans. Therefore,

OEHs HEV model is being applied to inform the Site Selection Criteria and

Mapping Methodology for the Rural Land Use Strategy.

The results of OEHs HEV methodology will be reported to

Council early 2016 meeting, along with the draft Rural Land Use Strategy for

consideration.

It is important to acknowledge that mapping is a reiterative

process and that any information gaps in the HEV model will be updated as new

information becomes available or when information changes such as amendments to

listed species under the Threatened Species Conservation Act.

Financial Implications

Nil

Statutory and Policy

Compliance Implications

The HEV methodology will be used to inform the Rural Land

Use Strategy, E Zones, and the review of the Biodiversity Conservation

Strategy.

Staff Reports - Sustainable Environment and Economy 5.2 - Attachment 1

Staff Reports - Sustainable Environment and Economy 5.2 - Attachment 2

Figure 1. Relationship of vegetation mapping review to

other projects

Figure 1. Relationship of vegetation mapping review to

other projects

Staff Reports - Sustainable Environment and Economy 5.3

Report No. 5.3 Wildlife

Corridor Mapping

Directorate: Sustainable

Environment and Economy

Report

Author: Sharyn

French, Manager Environmental and Economic Planning

File No: I2016/30

Theme: Ecology

Planning Policy and Natural Environment

Summary:

This report provides background information to the Committee

of the mapping methodology for wildlife corridors. The Biodiversity

Conservation Strategy sub group will meet to further discuss.

|

RECOMMENDATION:

That the Biodiversity and Sustainability Advisory

Committee note the report and that the Biodiversity Conservation

Strategy sub group will meet to discuss the review of the wildlife corridor

mapping.

|

Attachments:

1 Wildlife

corridor mapping, E2016/1421 ,

page 28

2 OEH

Priority Investment Areas Mapping Guide, E2016/4859

, page 34

Report

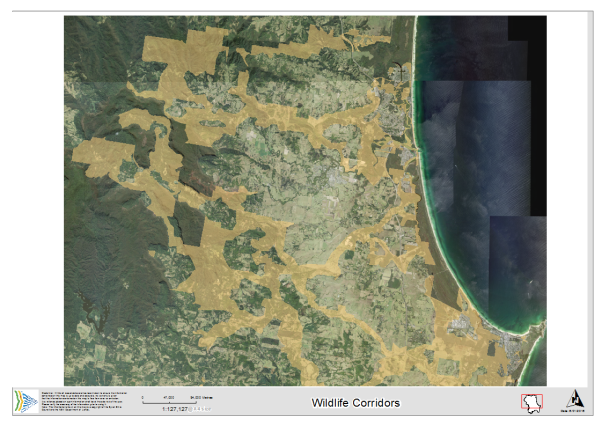

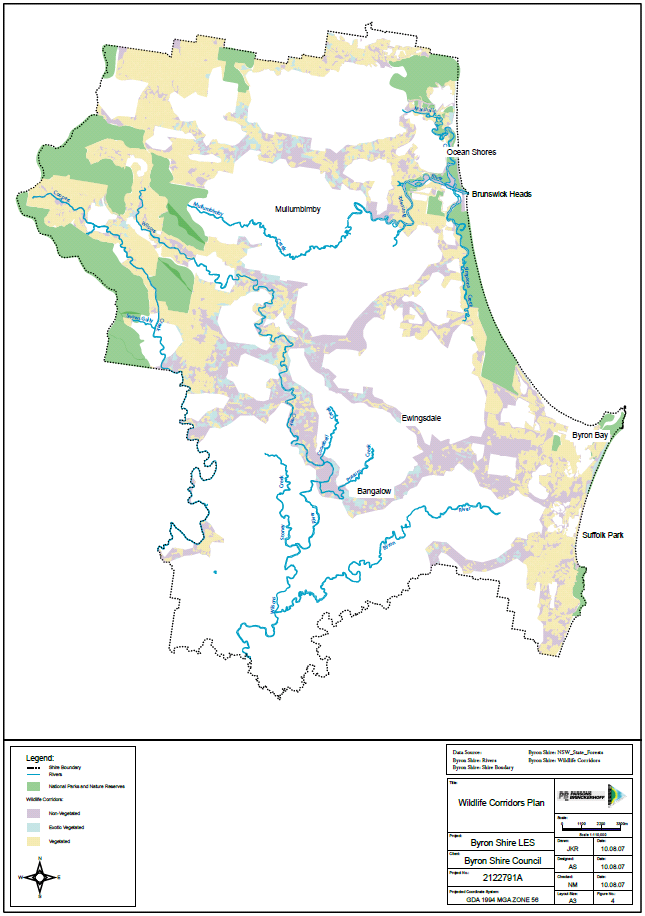

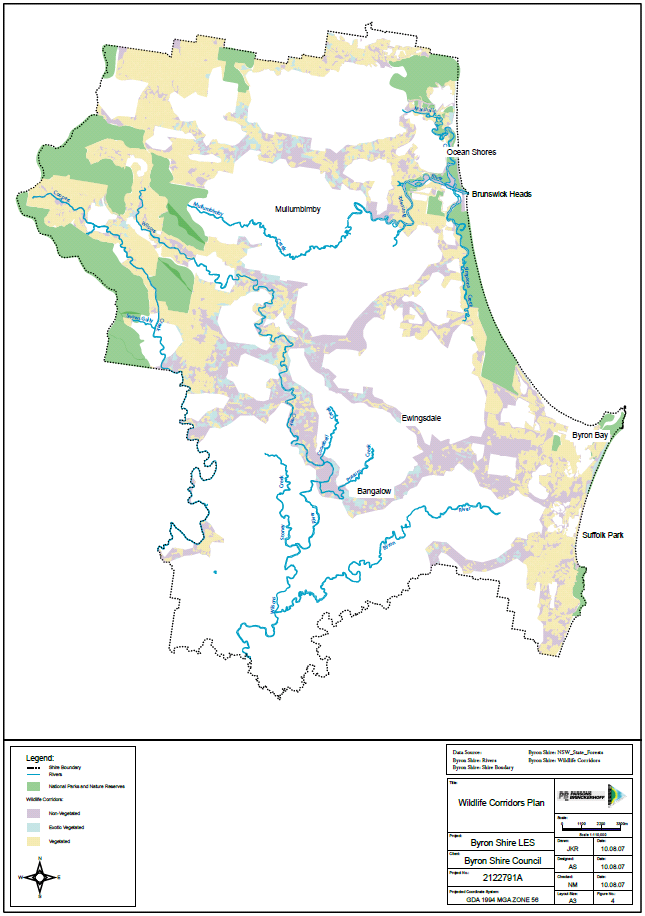

Byron Shire’s wildlife corridors were developed as

part of the Byron Biodiversity Conservation Strategy (BCS) 2004 and are based

on wildlife corridor mapping produced by National Parks and Wildlife Service

(NPWS). The NPWS mapping was refined by ecologists and botanists involved in

the production of the BCS based on detailed knowledge of the Byron Shire

landscape and the ecology of local fauna and flora species. Wildlife corridors

have been developed to identify important links across the landscape to

encourage the movement of flora and fauna species.

The current mapping represents existing, potential and

preferred habitat and corridors as a single layer. The original mapping

categorised the land as “primary corridors” comprising remnant

native vegetation and “secondary corridors” – cleared land

which lay in important connectivity locations as well as corridors dominated by

exotic vegetation such as camphor laurel. In 2007, the different

classifications were collapsed into a single GIS layer for wildlife corridors. (see

Attachment 1 – Figure 1A)

When viewing the mapped corridors, they appear as wide

avenues under which stricter environmental planning conditions apply. What this

fails to take into account is the different classes of corridor and the

difference between existing and potential habitat. While linear corridors with

continuous vegetation are the more recognisable form, stepping stones of

isolated patches of vegetation can still act as effective wildlife corridors.

For them to provide effective connectivity, however, the maximum distance

between them is generally accepted to be 100m (OEH factsheet).

Mapping methodology

Byron Biodiversity Conservation

Strategy 2004

Development of planning controls for wildlife corridors

Primary (existing native vegetation) and secondary wildlife

corridors (exotic vegetation and non-vegetated areas), were mapped from the

NPWS data and refined by BSC ecologists

Primary corridors were given an ecological value of 27,

deeming them HCV.

In developing planning controls

for secondary wildlife corridors Council had regard to the following.

· The

need to review Councils DCP (or similar planning control) for exempt and

complying development to ensure the appropriateness of any forms of development

in ‘secondary wildlife corridors’;

· All

identified wildlife corridors are to be afforded environmental protection

zoning and where possible enhanced;

· Clearing,

draining, filling or destruction of High Conservation Value vegetation or

habitats, vegetated wildlife corridors and threatened species habitat will not

be permitted unless there are no other alternatives;

· Development

of effective planning controls shall promote and allow for environmental repair

and enhancement and active management;

· Development

of effective planning controls shall maintain, protect and enhance corridor

values in order to facilitate the movement and dispersal of species across the

landscape;

· Development

of effective planning controls that control development that will impact on

potential corridor values;

· To

ensure that any development that occurs in a ‘secondary wildlife

corridor’ will be required to undertake environmental repair and

enhancement actions as part of that development (similar to that in the Byron

Rural Settlement Strategy with 900 trees per dwelling).

Development of mapped wildlife corridors

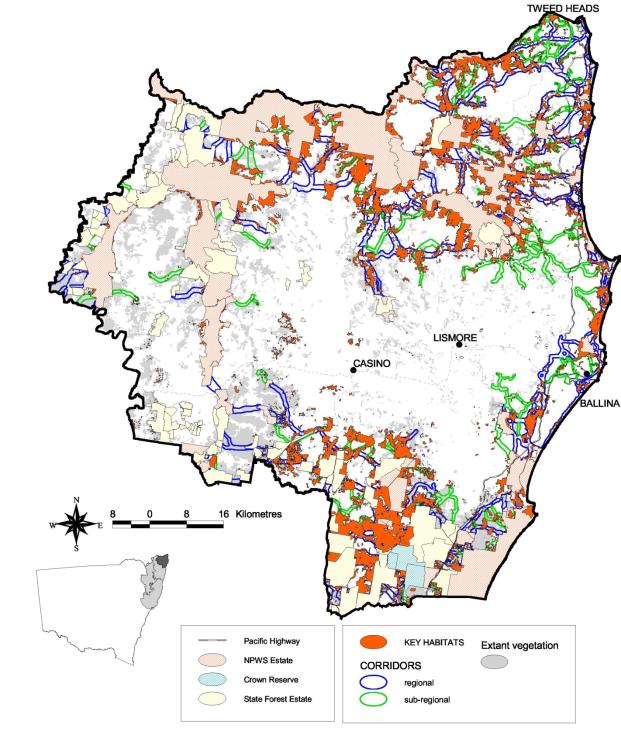

The NSW NPWS (now Department of Environment and Conservation

- DEC) prepared mapping of regional and subregional wildlife corridors for

north-east NSW (including Byron Shire), based on key fauna habitat modelling

and vegetation mapping (See Attachment 1 – Figure 2). This mapping was

refined by Council to better reflect on ground attributes (such as vegetation

cover and existing environmental protection zones). Regional corridors (greater

than 500m in width allowing migratory pathways across altitudes and latitudes,

thereby connecting regions such as coastal, hinterland and tableland

ecosystems) and subregional corridors (with vegetated landscape features such

as ridges and valleys requiring connection, preferably with corridors greater

than 300m wide) were then amalgamated to a single layer, with mapped rivers

(with a 20-metre buffer) added to include the main riparian corridors. (See

Attachment 1 – Figure 3)

Key notes from the 2003 NPWS

study upon which Council’s methodology is based:

· Corridors

are specific to a biological group for which likely preferred habitat can be

mapped (faunal assemblages).

· For

any particular assemblage, animals usually follow the path of least resistance

when moving through landscapes, and corridors are based on the best available

combination of a habitat hierarchy linking two patches of habitat.

· Corridors

are not necessarily continuous—they may be broken by currently degraded

or cleared areas but must contribute to overall landscape connectivity, or have

the potential to do so given restoration. Accordingly, stepping-stone patches

provide connectivity and can function as corridors for mobile species,

particularly those willing to cross expanses of cleared land (e.g. Date et al.

1991, 1996; Brooker et al. 1999; Eby et al. 1999).

· All

else being equal, wide corridors are better than narrow corridors but spatial

dimensions should reflect the demographic requirements of species that are rare

and that have specialized habitat and foraging requirements. The requirements

of wide-ranging species (e.g. nomads and migrants) are also important (Dobson

et al. 1999).

· Corridors

spanning natural spatial gradients (e.g. altitudinal and latitudinal gradients)

are critically important in the context of ecological processes and climate

change. Species acting as vectors for ecological processes (e.g. propagule

dispersers, predators) require special consideration;

· Sub

– regional corridors are landscape corridors that serve more as routes

for dispersal and movement for assemblage reference species and wide-ranging

species, rather than habitats in their own right.

Neighbouring Councils’ mapping methodology

Lismore

In producing their Biodiversity Conservation Strategy (BCS),

Lismore Council engaged Landmark Ecological Services to produce a study based

on the mapping of key habitats and corridors (http://www.lismore.nsw.gov.au/page.asp?f=RES-CVI-50-43-25

). Vertebrate fauna and their habitat were used as surrogates to determine

overall biodiversity values and to identify and rank key habitats and

corridors. Key habitats were identified using vegetation mapping developed in

2011, mapping of watercourses and soils, vertebrate records from the Atlas of

NSW Wildlife (OEH, Sydney) and previous corridor mapping undertaken for the

LGA. Key habitats were identified and ranked on the basis of their known or

potential value as habitat for threatened species and for other

conservation-priority species with core habitat in the Lismore LGA.

The study compared its mapping methodology to the former

Catchment Management Authority (CMA) mapping, and resolved habitat types to a

finer scale. It also contained prioritisation for rehabilitation and

preservation of habitat and corridors, and their ranking in terms of their

significance in achieving these outcomes.

This is by far the most comprehensive effort amongst the

surrounding councils to map corridors. The information was provided under a

subheading of Urban Green Corridors Plan within the BCS.

Tweed

The Tweed Council’s two staff concerned with

environment are on leave till 18 January. A search of their website and phone

contact revealed very little information on wildlife corridors. The only

mention was within their recently released CKPoM. No mapping or methodology was

detailed or known, with references only to the need to provide corridors for

koalas without any management actions provided. Mapping identified habitat with

no corridors identified.

Work on a biodiversity management plan is ongoing, with the

potential for inclusion of vegetation mapping which factors in connecting

corridors.

Ballina

Ballina Council has utilised the NPWS mapping to inform

their corridor identification in their DCP 2012. Due to staff leave

arrangements, there is no information available till after the 18 January as to

methodology which may have been more recently employed for vegetation mapping.

No further information is available on their website.

State planning

OEH is developing two mapping categories for future land

management; Priority Investment Areas (PIA) and High Environmental Value (HEV).

PIA are sites where funding for biodiversity management can

make the greatest difference for biodiversity and typically include large

remnants and biodiversity corridors (See Attachment 2). These priority areas

will assist funding bodies in identifying preferred locations to invest

biodiversity funds. The North Coast mapping is currently classified as

“near completion”.

The corridors identified as PIAs include only those of state

and regional significance. While corridors of local significance play an

important role for connectivity, they are not identified as PIAs and the

identification of local corridors remains the responsibility of local

government and Local Land Services, through Local Environmental Plans (LEPs)

and other mechanisms.

This differs from HEV which are areas that contain values of

particular significance that are considered for protection under statutory

instruments. The HEV criteria are used by OEH Regions to construct an

HEV map for submission to the Department of Planning & Environment (DPE)

for inclusion in Regional Growth Plans (RGPs) (See separate report on HEV for

methodology).

A landowner’s rights to carry out activities such as

agriculture and development are not altered by their property being identified

within a PIA; it is not a constraint but rather an opportunity to attract

funding for critical habitat restoration and preservation. PIA’s may

however comprise areas of HEV. Landuse planning should be informed by HEV

mapping, and the use of PIA mapping as the base layer for land use planning is

not recommended.

One of the key corridor projects in NSW is the Border Ranges

Alliance in the Great Eastern Ranges corridor. An independent report to the

Interstate Agency Working Group convened under the Environment Heritage and

Protection Council/Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council provides

comprehensive detailing of the rational of and need for wildlife corridors. See

http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/resources/nature/ccandger.pdf

for the paper.

National level

The previous government produced a National Wildlife

Corridors Plan: a framework for landscape-scale conservation in 2012. (https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/e73bc1c8-81f0-4800-8f1a-3fb6cb7558ac/files/national-wildlife-corridors-plan.pdf

) In its own words “The Corridors Plan represents the

Australian Government’s commitment to retain, restore and facilitate

active management of corridors and natural patterns of vegetation, waterways

and other landscape features across public and private lands, through our

cities and towns, and between our national parks. Through the Corridors Plan,

cooperative, voluntary action on the part of all land managers to restore

ecological connections throughout the landscape is supported—be it farm

land, urban land, conservation areas or Indigenous land that is being

managed.”

The plan stressed the importance of wildlife corridors in

assisting species survive the impacts of climate change, and seeks to increase

community participation in wildlife corridors and connectivity conservation.

Examples of current local on ground work

Land for Wildlife – restoring rainforest in a

biodiversity hotspot

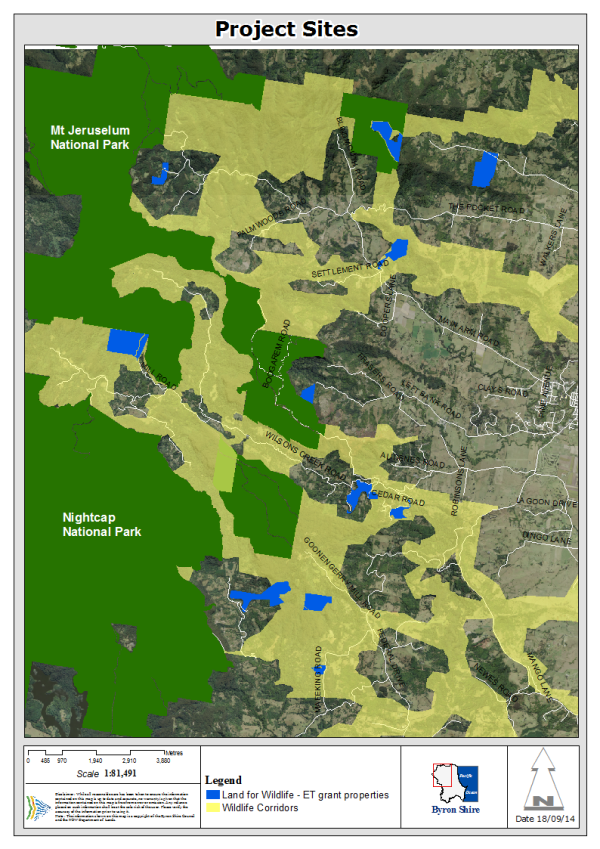

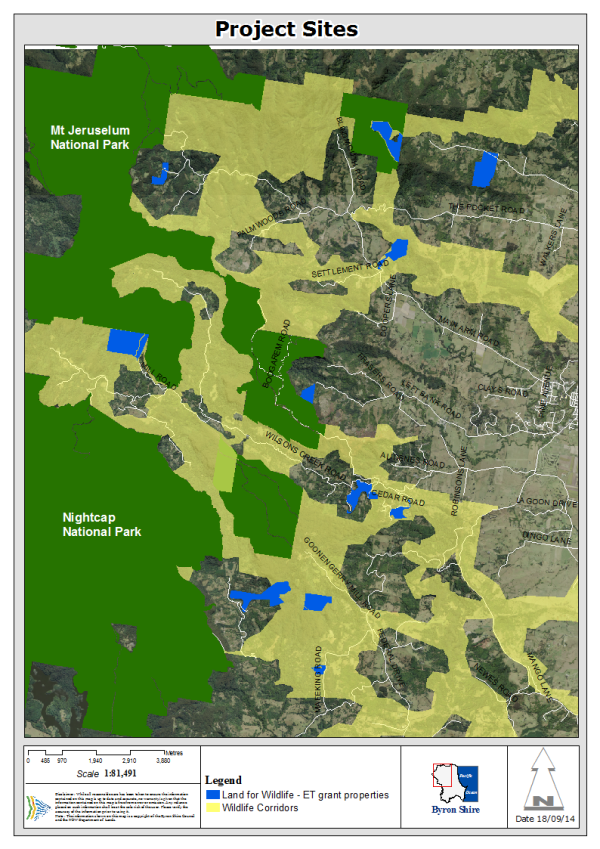

In collaboration between Council, NSW Environmental Trust (ET)

and local Land for Wildlife members, weed control, tree planting and native

fauna nesting box deployment is occurring across 11Ha on 11 properties.

Currently entering its second year, this ongoing project is funded by Council

and ET grant ($99,000). The majority of the properties lie within areas

currently mapped by Council as wildlife corridor. (See Attachment 1 –

Figure 4)

The project is categorised by ET under Vegetation

corridors/Vegetation management and feedback from ET prior to the delivery of

the second year of funding included “The achievements so far in the

on-ground component of the project are excellent. The Grantee is targeting high

priority areas identified in the Border Ranges Biodiversity Management Plan and

then using work plans to guide on-ground work.”

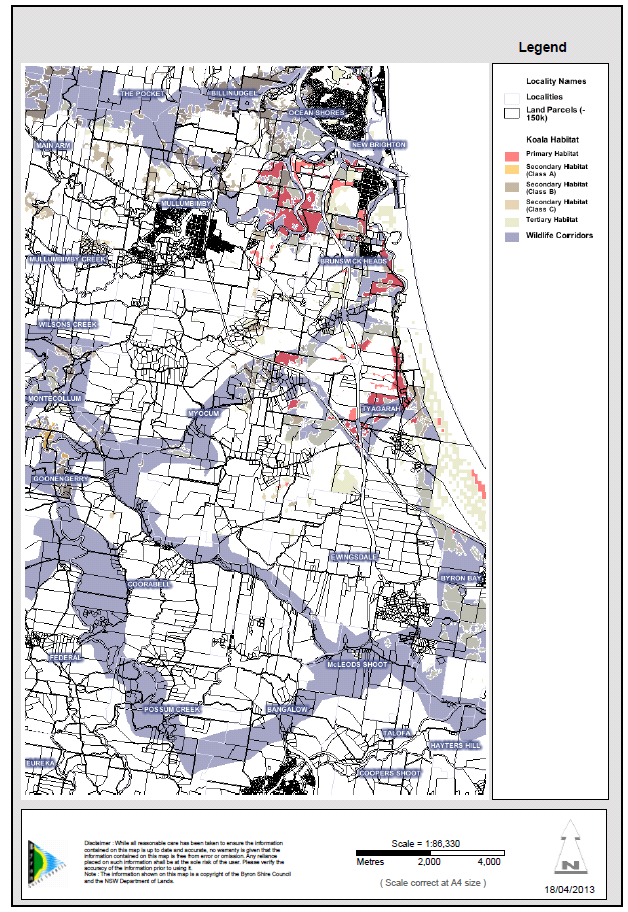

Koala Connections

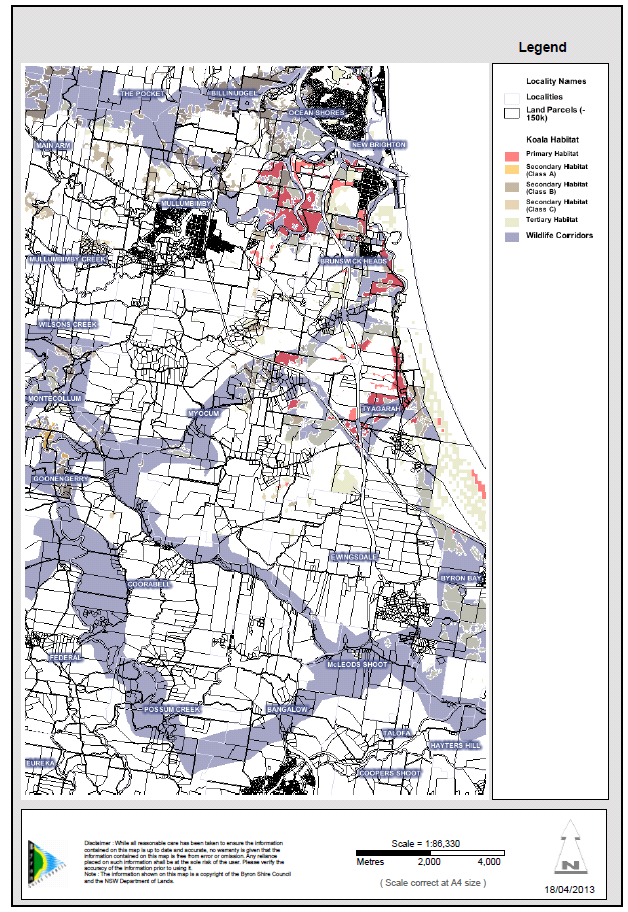

Guided by the Tweed and Byron Coast Koala Habitat Studies by

Dr Steve Philips, the project will improve north-south and inland to coastal

indicative koala linkages, and improve ecosystem resilience and adaptation to

climate change. The project works will enhance the wildlife corridors of Byron

Shire, improving the linkages between the hinterland koala populations of the

Huonbrook - Wilsons Creek area, and the coastal populations near Tyagarah.

Where habitat connections are through many small holdings, several neighbours

are working together under the Koala Connections program, to develop a strategy

for on ground works. Action plans will provide the guidance for each site to

rebuild the habitat. Attachment 1 – Figure 5 shows the overlap between

current primary koala habitat and class A secondary habitat with the wildlife

corridors.

Background Overview – sourced from OEH

Habitat loss and fragmentation are the two main contributors

to continuing biodiversity decline across the landscape. Wildlife corridors may

be a key tool in slowing or possibly reversing this trend.

While stepping stone fragmented habitats may be of some use

to birds and mammals able to fly, linear corridors provide a more comprehensive

protection for enabling the movement of plant, fungi and animal species. The

maximum separation distance for patches to provide connectivity and act as a

corridor is generally accepted to be 100 metres.

Corridors are critical for the maintenance of ecological

processes including facilitating the movement of animals and the continuation

of viable populations. This is particularly important for ensuring genetic

diversity within species. Communities with isolated gene pools can become

susceptible to inbreeding, while potentially losing resilience to survive

impacts from habitat loss and disease outbreak. Corridors also allow for

greater recolonisation post impact.

In helping species adjust to climate change impacts by

allowing altitudinal and latitudinal movements, promoting the increase in

corridors also potentially makes a contribution to increasing carbon store

capacity of a region while improving water quality and flow patterns in

catchments. This can reduce impacts of erosion over the longer term.

Many animals are also vital for the fertilisation of plant

species, particularly rainforest trees. The inability of native fauna to reach

isolated remnant ecosystems may lead to local extinctions. Fragmented habitats

also become more susceptible to issues such as arise from edge effects, where

weed species are able to infiltrate the remnant. Wider corridors are more

resilient and can act as habitat in their own right.

Regionally, it is important to maintain corridors greater

than 500m in width. This can allow migratory pathways across altitudes and

latitudes, thereby connecting regions such as coastal, hinterland and tableland

ecosystems.

On a sub-regional scale, vegetated landscape features such

as ridges and valleys require connecting, preferably with corridors greater

than 300m wide.

Locally, corridors provide important connections amongst

remnant patches of vegetation and landscape features such as creek lines,

gullies, wetlands and ridges.

Conclusion

The current Council wildlife corridor mapping was developed

as part of the Byron Biodiversity Conservation Strategy (BCS) 2004 and is based

on wildlife corridor mapping produced by National Parks and Wildlife Service

(NPWS) refined by BSC ecologists.

The corridors are vital connectivity measures facilitating

species movement across fragmented habitat. They act to limit species loss by

providing resilience for genetic diversity, assist population recovery post

fire/flood and reduce negative impacts of climate change by allowing movement

to more suitable habitat.

Future mapping may be more readily accepted by the

landholders if corridors were categorised as existing or potential. It would be

good to prioritise supporting riparian and ridgeline revegetation over paddock

scale projects, as these are both frequented habitat for wildlife and more

likely to gain the cooperation of landowners. Funding such as for the Land for

Wildlife project may then be more readily acquired through PIA mapping.

The most detailed and comprehensive corridor mapping for a

neighbouring council at present is that produced by Landmark for Lismore LGA.

Future mapping should coordinate Byron corridors with Lismore, Tweed and

Ballina corridors.

State government moves from HCV to HEV classification are

reflected in new mapping methodology. PIA mapping (near completion) will

assist in prioritising areas for biodiversity protection, but should not be

used for future wildlife corridor mapping.

Financial Implications

Nil

Statutory and Policy

Compliance Implications

The review of the Biodiversity and Conservation Strategy

will consider a methodology for wildlife corridors.

Staff Reports - Sustainable Environment and Economy 5.3 - Attachment 2

Attachment

1

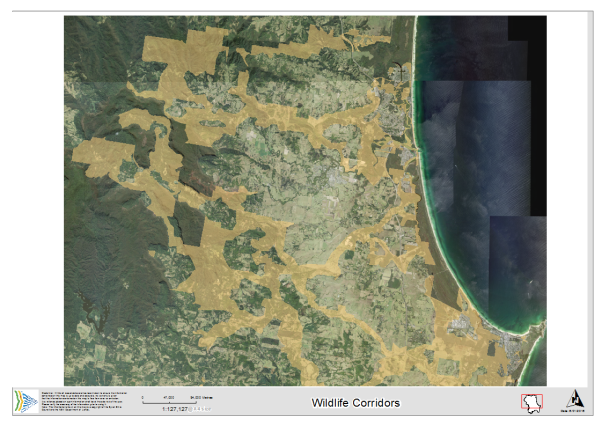

Figure 1 A)The current wildlife corridor

mapping built from NPWS input and Council’s 2007 vegetation layer.

Figure 1 B) Corridors combined with HCV layer

Figure 2: Key habitats and

wildlife corridors of north east NSW – NPWS

Figure

3:

The original NPWS corridors with Council’s adjusted corridor mapping

overlaid.

Figure

4 The

Locations of properties involved in the Council - ET Trust – Land for

Wildlife project.

Figure 5 Koala habitat

identified within the Koala Connections project in relation to current wildlife

corridors.

Figure 6 The wildlife corridor plan prior to

the collapsing of the layers as shown in Figure 1A

Priority Investment Area Use

and Mapping Guide

06/05/2015

Staff Reports - Sustainable Environment and Economy 5.3 - Attachment 2

Contents

Contents. 1

Executive summary. 2

1 Introduction. 3

2 Policy

context 4

3 Use of

PIAs. 7

3.1 Principal uses. 7

3.1.1 A decision

support tool for grant providers. 7

3.1.2 Guiding

expenditure through offset funds. 7

3.2 Relationship to other

programs. 8

3.2.1 Supporting Local

Land Service programs. 8

3.2.2 Supporting local

government programs. 8

3.2.3 Supporting

community organisations and projects. 9

3.2.4 Reserve

establishment 9

3.2.5 Saving our

Species Program.. 10

3.3 Relationship to strategic

planning and development assessment 10

3.3.1 Strategic

planning. 10

3.3.2 Development

approval processes. 11

4 PIA

mapping standards and guidance. 12

4.1 Features included in

Priority Investment Areas. 12

4.1.1 Core areas. 12

4.1.2 Biodiversity

corridors. 12

4.2 Mapping standards. 14

4.3 Mapping guide. 15

Staff Reports - Sustainable Environment and Economy 5.3 - Attachment 2

Executive summary

Priority Investment Areas (PIAs) identify areas where

funding for biodiversity management can make the greatest difference for

biodiversity. PIAs comprise of core areas of vegetation and biodiversity

corridors that are important at a state and regional level. These

priority areas will assist funding bodies in identifying preferred locations to

invest biodiversity funds. They may also provide useful information for land

owners and land managers on the areas that have an increased potential of

receiving biodiversity management funds.

PIAs are not developed for the

purpose of informing land use planning or development applications and are not

intended to be used for land use planning purposes. A landowner’s right

to carry out activities such as agriculture and development is not altered by

their property being identified within a PIA.

A consistent and repeatable

approach to the identification and mapping of PIAs across NSW is required to

ensure equity in the mapping produced. Landowners within the Priority

Investment Areas may be preferentially targeted to receive financial benefits

if they protect bushland compared to landowners outside these areas. It

is important, therefore, that the identification of these priority areas is

transparent and follows a consistent approach.

This document provides overarching mapping standards

to guide the preparation of PIA mapping. Mapping guidance is provided for core

areas, state biodiversity corridors and regional biodiversity corridors. The

document sets minimum standards for the quality of both input and output data,

whilst allowing for differences in regional data availability and land use

pressures. To summarise, the guide

requires the mapping of PIAs to:

· Draw on existing data sources where information is

available and suitable;

· Be mapped at a property scale;

· Be prepared with local knowledge, validation and

consultation.

PIA mapping has not yet been

completed for all regions in NSW. In regions where mapping is not

available, OEH will continue to base biodiversity investment decisions on

available environmental information as is current practice.

1 Introduction

Priority Investment Areas

(PIAs) identify areas where funding for biodiversity management can make the

greatest difference for biodiversity. The PIAs include:

· core areas,

large remnants where management will contribute the greatest benefit to the conservation

of key state and regional biodiversity values within a region; and

· state and regional biodiversity corridors, linear areas which link core areas and play a

crucial role in maintaining connections between animal and plant populations

that would otherwise be isolated and at greater risk of local extinction.

Government regularly makes

funding available to support biodiversity management actions through various

grant programs and it is committed to ensuring that these funds are spent in an

effective and accountable way. Identifying priority areas for biodiversity

investment is one way of ensuring that funds are targeted to areas of greatest

strategic benefit, based on an assessment of broad scale biodiversity and

stakeholder values.

PIAs will be used in two ways.

Firstly, to inform funding bodies of preferred locations to invest biodiversity

funds. Secondly, it may provide useful information for land owners and land

managers on the areas that have an increased potential of receiving biodiversity

management funds. As such, being mapped in a PIA may increase the

opportunities for landowners to receive funding to protect their bushland, but

participation in any funding program is entirely voluntary.

PIAs are not developed for the

purpose of informing land use planning or development applications and are not

intended to be used for land use planning purposes. PIAs do not identify all

significant vegetation, and therefore it cannot be assumed that areas not

identified as a PIA are of lower environmental value.

A landowner’s right to

carry out activities such as agriculture and development is not altered by

their property being identified within a PIA. Areas within PIAs may have

environmental values (including areas that also conform to the HEV criteria)

that may need to be considered as part of existing statutory planning and

development approval processes, and would require an appropriately scaled level

of environmental assessment as specified by the relevant planning or consent

authority. The identification of land as a PIA does not alter these

existing requirements in any way.

PIA mapping is currently not

available in all regions in NSW. In regions where mapping is not

available OEH will continue to base biodiversity investment decisions on available

environmental information as is current practice.

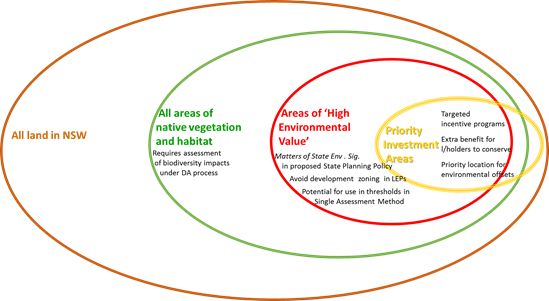

2 Policy context

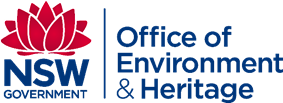

Land of biodiversity value in

NSW may be categorised into a series of sub-groups for land use and

conservation planning purposes (Figure 1). Within NSW, all areas of native

vegetation and habitat require an assessment of biodiversity impacts under

the development application process[2].

A subset of these areas,

termed areas of High Environmental Value, contains values of particular

significance that are considered for protection in statutory processes.

It includes, for instance, land containing threatened ecological communities,

habitat for threatened species, important wetlands and protected areas.

The term High Environmental Value is equivalent to the terms

‘State and regional biodiversity value’, ‘High Conservation

Value’ or ‘Environmentally Sensitive Areas’.

The Office of Environment and

Heritage (OEH) recommends that areas of ‘High Environmental Value’

be identified and considered for protection through all land use planning

processes, including growth strategies and regional and local plans.

Further guidance in relation to land use planning is provided in Section 3.3.

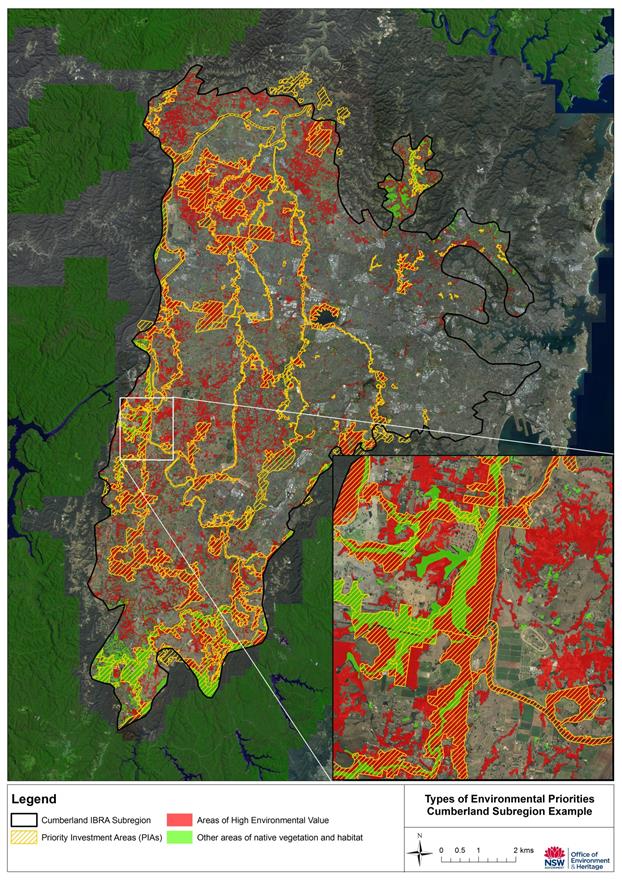

Figure 1: Relationship

of Priority Investment Areas to areas of High Environmental Value and other

native vegetation1

Priority investment areas are geographically the smallest subset of

environmental priorities. PIAs generally consist of areas of High

Environmental Value, however on some occasions may also include areas of native

vegetation and habitat or, where cleared land is identified in a PIA, may also

include other land in NSW. PIAs are recommended by OEH as the

priorities for biodiversity funds.

Priority investment areas

are not a ‘retention target’. They do not represent the only biodiversity values

that should be protected through planning and development

processes. As described above, planning and development approvals

need to consider retaining and protecting a broader range of biodiversity

values wherever feasible, especially those areas of High Environmental Value.

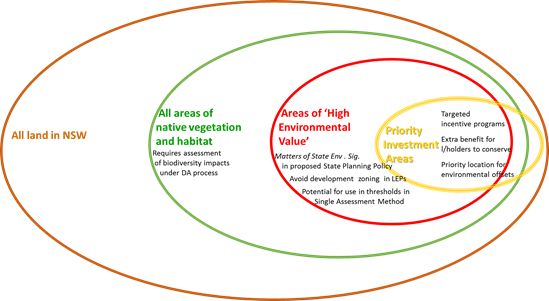

Figure 2 provides an example from Western Sydney of how PIAs,

areas of High Environmental Value and areas of native vegetation

interact. The figures show that a significant amount of High

Environmental Value vegetation and habitat can occur outside the mapped

PIAs. This is possible as the PIAs identify only the best available areas

for biodiversity investment, not all environmentally sensitive areas.

Figure 2 demonstrates the importance of identifying both PIAs

and areas of High Environmental Value. This information can then be used, as

required, to provide input into a range of biodiversity investment, land use

and conservation planning processes.

Figure 2: Example

of Priority Investment Areas and High Environmental Value mapping in western

Sydney

Note: Areas of HEV may be excluded from PIA mapping for a

number of reasons, including vegetation condition, vegetation type and existing

or planned land use.

3 Use of PIAs

PIA mapping provides a

single, accessible map that identifies the best areas for strategic investment

in biodiversity management.

3.1 Principal uses

Federal,

state and local governments regularly make funding available to support

biodiversity management actions through various grant programs and are

commitment to ensuring that these funds are spent in an effective and

accountable way. Identifying priority areas for biodiversity investment is one

way of ensuring that funds are targeted to areas of greatest strategic benefit,

based on an assessment of broad scale biodiversity and stakeholder

values. The availability of PIA mapping can assist a large number of

stakeholders by providing information related to the location of biodiversity

priorities.

3.1.1 A

decision support tool for grant providers

By

investing in the PIAs, fund managers can be confident that they are

contributing to strategic conservation outcomes that have a level of broad

based stakeholder support.

PIA

mapping can be utilised in different ways depending on the objectives of the

grant funding program. For example, a program may target only

biodiversity core areas or only corridors within the project area.

Programs targeted toward specific features or landscape units can use the PIA

mapping as an initial filter to target areas for investigation.

OEH

recommends that program funding be preferentially targeted to land that is

within or partially within the PIAs. Methods to achieve this include a

weighting (e.g. 10 – 25%) that is applied to grant applications that are

located within, or partially within, a PIA. This enables applications

outside of the priority areas to also be competitive if they provide other

benefits.

As would

be expected, a grant program would need to undertake site based assessments to

ensure that the land has the specific features that are targeted for funding.

3.1.2 Guiding

expenditure through offset funds

The rules

and governance framework associated with the major projects offset fund are

currently being prepared.

The

availability of a central offset fund provides OEH (and any nominated fund

manager) an opportunity to achieve strategic environmental outcomes by

targeting expenditure to priority locations. The use of an offset fund by

proponents may also lead to scrutiny of the fund manager, and the processes

followed to obtain and secure biodiversity offsets. An approach that

demonstrates that offsets are being obtained using a transparent approach from

high priority sites may therefore be beneficial.

It is

proposed that the mapped PIAs be part of the governance framework for the

offset fund to demonstrate that offsets are being obtained from strategic

locations which provide the greatest benefit to conservation. Under this

framework, the offset fund must locate offsets within PIAs as a first

preference before other land is considered. Further criteria can be used

to prioritise land within the PIAs. For example, like for like, IBRA subregion

or credit profile requirements can be identified within the PIAs to target

funding towards the values required to offset a particular impact. The Growth

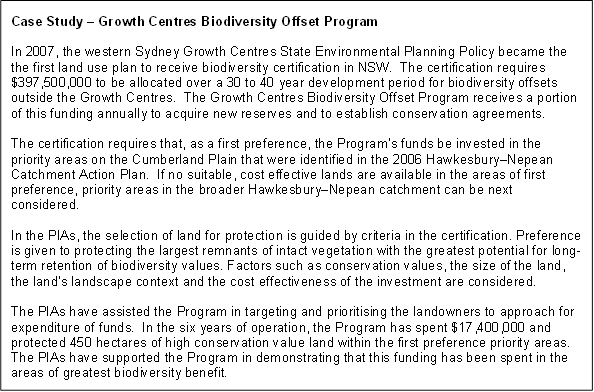

Centres Biodiversity Offset Program is an example of this approach (case study

below).

3.2 Relationship to other

programs

3.2.1 Supporting

Local Land Service programs

Local Land Services (LLSs)

identify regional and local priorities in their Catchment Action Plans (CAPs)

to guide their expenditure of funds. In some circumstances the locations

identified in a CAP may differ from those identified in PIA mapping due to

differing mapping approaches and objectives.

Depending on the purpose of

the funding stream, the LLS is encouraged to consider PIAs in the expenditure

of funding. This may include prioritising, as a first preference, funding

to areas where the PIAs over-lap with the CAP priorities, before considering

investment in other areas.

It is acknowledged that the

LLS may have different purposes for funding than those identified by the PIAs,

or may be able to achieve positive biodiversity outcomes outside mapped PIAs.

3.2.2 Supporting

local government programs

Consultation with

councils has identified the benefit of a strategic, regional context of

biodiversity priorities to support local biodiversity management planning and

prioritisation. The PIAs provide a resource to support the establishment

of local priorities by councils.

Councils are able

to build on the identified PIAs within their LGA, enhancing the network of core

areas and corridors identified with lands of local biodiversity importance in

their council area, such as local corridors. PIAs may also be of

assistance to local government in the preparation of local documents (such as

biodiversity strategies) or in the prioritisation of effort in applying for

grant funding.

Council can

utilise the information to determine if any council owned sites are identified

as PIAs, thus increasing the potential to receive funding to manage or conserve

these areas. Council may also wish to prioritise PIAs in the expenditure

of their own funds, where local and regional priorities align.

3.2.3 Supporting

community organisations and projects

PIA mapping

provides community groups with information related to biodiversity investment

priorities that can assist in the selection of appropriate sites to expend

effort. As PIAs have an increased chance to receive funding, and

contribute to a wider network, community groups can choose to focus on these

areas when considering applications for grant or other funding. This may be

particularly relevant to new groups, or existing groups looking for new sites

or opportunities.

PIA mapping does

not identify all areas of state or regional priorities, nor does it identify

areas of local value. Groups working outside of identified PIAs continue

to provide a positive benefit for biodiversity within the study area.

3.2.4 Reserve

establishment

Addition of land to the

National Parks estate occurs in accordance with the principles of the National

Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 and corresponding Government policy namely, the

National Parks Establishment Plan (currently under review and publicly

exhibited as the ‘Directions Statement for National Park

Establishment’). Additions in the medium term are prioritised

towards better landscape connectivity, improving reserve design and management

and areas of cultural importance[1].

Other long-term conservation themes include poorly reserved ecosystems,

wetlands and riparian features, water catchments and areas of

geodiversity.

The PIA

map is one of many sources of information that support the reserve

establishment process. The PIA map provides this support by identifying

core areas of poorly reserved ecosystems and State and regionally significant

corridors. There are a range of other values that are important for

reservation and so not all new reserves or additions to existing reserves will

occur in PIAs.

The PIA

map is therefore not a ‘plan’ for building the reserve

system. Land identified on the map is not necessarily suitable for

reservation. The land may however be suitable for other management

opportunities, such as grant funding to land owners.

3.2.5 Saving

our Species Program

The PIAs do not identify all

state and regional priority areas. For instance, the Saving our Species program provides additional priorities for areas of

value for threatened species management.

It is expected that the purpose of the

funding will determine which priority areas are best suited for guiding

investment. Investment in threatened species management is best

prioritised through the Saving our Species Program. Government offset and

grant programs which aim to achieve the greatest benefit for vegetation

management are best prioritised through the PIA mapping.

3.3 Relationship to strategic

planning and development assessment

3.3.1 Strategic

planning

The primary information provided by OEH

for considering biodiversity values in land use planning processes is the

mapping and criteria for High Environmental Values (HEV). OEH recommends

that areas of HEV be identified and considered for protection through all land

use planning processes, including growth strategies and regional and local

plans.

Priority investment areas are

not suitable for use in land use planning processes in lieu of consideration of

the HEV map, or other appropriate landscape-scale assessment of biodiversity

values. This is because the PIAs do not identify all areas of high conservation

value and also because it includes areas in a range of conditions.

The PIA map will be publicly available and

it is recognised that planning authorities may have an interest in considering

the map in land use planning, particularly for the identification of

‘corridors’ which are not included within the definition of

HEV. The following advice will accompany the PIA mapping to ensure that

it is not used inappropriately:

· Land use planning should be informed by the HEV layer

provided by OEH. OEH does not warrant the use of the PIA map as being suitable

for land use planning purposes in isolation from the HEV map.

· If a Planning Authority intends to use the PIA

mapping, it is required to undertake a process of validation and amendment of

the data, including consulting with stakeholders on the accuracy of the mapping

and its intended use.

· Validation of PIAs is likely to include re-evaluating

the boundaries of core areas and corridors to take into account changes in the

extent of vegetation since the PIA Map was prepared. It may also include

adding or removing areas due to the outcomes of the planning process including

responses to public consultation, or alignment of areas with boundaries more

consistent with land use planning, such as cadastral boundaries.

· If a Planning Authority incorporates biodiversity

information into a land use plan through the above process, then responsibility

for the interpretation and use of the revised layer rests with the Planning

Authority. The revised data is different from OEH’s PIA map and being

used for a different purpose.

In some regions of the state, councils

have already incorporated corridor mapping into strategic plans, including

LEPs. Such regions include the Illawarra and the South Coast. In these

circumstances OEH recognises that the corridor mapping has been validated by

the council in consultation with stakeholders as part of the land use planning

process.

If corridors have already been adopted for

use by planning authorities, including those prepared consistent with the

guidance listed above, then OEH recognises this layer as being developed for

planning purposes and may support the council’s stated planning uses for

the map. OEH may also support the use of this map in regional plans and growth

strategies and to inform the use of appropriate provisions in local plans.

3.3.2 Development

approval processes

Priority

investment areas are not suitable for use in development assessment processes.

Assessments must be undertaken in accordance with the statutory requirements

applying to the particular proposal. Through the assessment process

consideration should be given to protecting all areas of High Environmental

Value, as well as areas of local biodiversity value.

A

landowner’s right to carry out activities such as agriculture and

development is not altered by their property being identified within a

PIA. Areas within PIAs may have existing environmental values (including areas that also conform to the HEV criteria) that

may need to be considered as part of existing statutory planning and

development approval processes, and would require an appropriately scaled level

of environmental assessment as specified by the relevant planning or consent

authority. The identification of land as a PIA does not alter these

existing requirements in any way.

OEH

recommends that the Biobanking Assessment Methodology and the Framework for

Biodiversity Assessment (or any future methodology) be used where appropriate

to guide development approval decisions. These methods provide guidance

on offset requirements and on areas that cannot be cleared and offset.

4 PIA mapping standards and guidance

4.1 Features included in Priority

Investment Areas

Priority

Investment Areas identify high priority biodiversity assets (‘core

areas’), state biodiversity corridors and regional biodiversity

corridors. Combined, these features are termed ‘Priority Investment

Areas’.

4.1.1 Core

areas

Core areas

of native vegetation and habitat where management will contribute the greatest

benefit to the conservation of state and regional biodiversity values within a

region.

Areas

considered for inclusion as core areas may include a variety of significant

biodiversity features, for instance, State and Commonwealth Threatened

Ecological Communities (TECs), under-reserved vegetation types, over-cleared

vegetation types, vegetation types present in over-cleared landscapes, significant

vegetation remnants, significant threatened flora and fauna habitat and large

and well connected and configured patches of native vegetation. Core

areas may also include other biodiversity values that may be important

regionally, such as endemic vegetation communities or habitat for endemic

species, important wetlands (Directory of Important Wetlands in Australia

(DIWA), State Environmental Planning Policy 14 (SEPP 14)), karst areas,

old-growth forest, rainforest, Commonwealth listed Matters of National

Environmental Significance (MNES), areas listed in statutory conservation or

protection mechanisms (such as State Planning Policies) and significant sites

identified by the community.

The core

areas will contain a subset of these biodiversity features at locations which

are likely to have:

· high long-term viability (due to their patch size,

condition, landscape position, connectedness and current/planned future land

use), and/or

· other unique or significant features.

Core areas

can be identified and mapped in a number of different ways. Where regional data

exists on conservation priorities, then this data may be included where it